How 'Ro Farah' mastered bipolar disorder to embrace London Olympic legacy

Rohan Kallicharan has gone from mental health crisis to the cusp of 100 marathons

Much is spoken about the legacy of the 2012 London Olympics, a sporting spectacle estimated to have brought £13bn worth of investment into the British capital.

In the days before Covid and Brexit, film director Danny Boyle pulled together an opening ceremony of such perfect Britishness that the Queen and James Bond shared top billing.

While celebrating the country’s traditions, Boyle’s masterpiece also championed the multi-cultural nature of the country.

It was a diversity that was reflected in the performance of the Great Britain team, with gold medals for the likes of Chris Hoy, Nicola Adams, Jess Ennis and Anthony Joshua.

But perhaps the most celebrated winner was a Somali refugee who had rebuilt his life in his adopted country.

Sir Mo Farah captured the 5,000m and 10,000m double to send Britain into raptures.

One of those wowed by the Games was Rohan Kallicharan. Weighing more than 19 stone, unable - in his own words - to “run a bath,” and recovering from years of mental health crisis, Rohan would use the power of London 2012 to help him launch his own spectacular running journey.

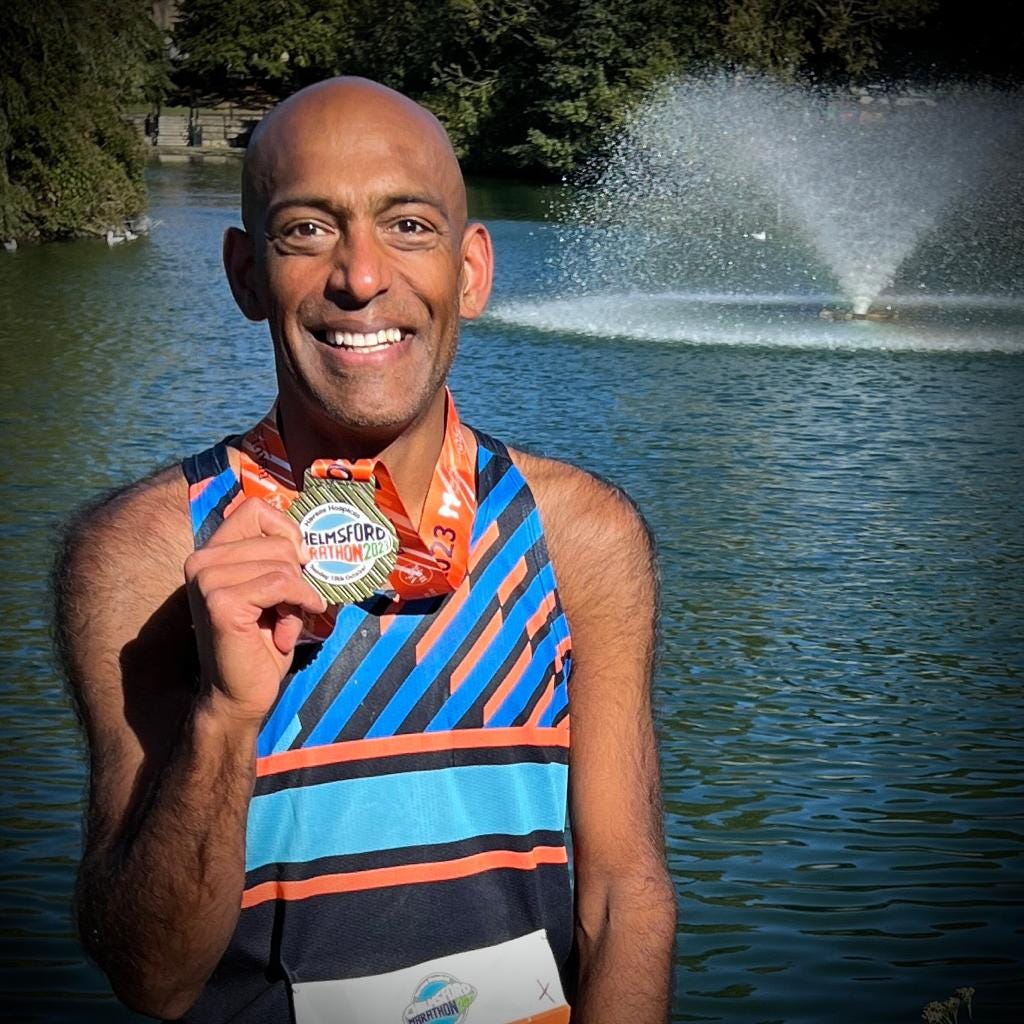

His discovery of running would lead work friends to give him a new nickname: Ro Farah.

In the decade since, he has run 82 marathons, clocked a fastest time under three hours and raised more than £45,000 for Mind, the mental health charity.

He is now closing in on the incredible achievement of reaching a century of marathons before he reaches his 50th birthday next year.

But Rohan’s greatest accomplishment came years before he caught the marathon bug, before London even thought of welcoming the Olympic Games, and back at a time when the mental health battle he was forced to fight came with the stigma of alleged weakness and inferiority.

Things had started to unravel for the young Rohan when he was just 17.

The son of West Indian cricket legend, Alvin Kallicharan, he had grown up in a sporty environment playing rugby, cricket and hockey at a good level.

But all that slowly disappeared as his life was overtaken by struggles with his mental health that left him unable to maintain a job or relationship.

In the 15 years that followed, Rohan attempted suicide three times. It was only when he was in his early 30s that he was finally diagnosed with bipolar disorder.

The vital news came after he was discharged from hospital following his third suicide attempt. It was the first time he had been referred to a psychologist, a move which he says probably saved his life.

“I remember I sat with him and we pictured the fact that for the next 12 months I was literally going to be a baby in the body of a man,” he said.

“From the age of 17 or 18, when I’d really begun to fall ill or at least when the illness began to demonstrate itself, all I'd known was a car crash.

“In my adult life up to that point I'd never been able to hold down steady employment, I'd never been able to pay the bills, I'd never been able to put food on the table. I had never been able to go two or three days without an acute episode either of manic behaviour or depression.

“As it turned out my diagnosis would be rapid cycling bipolar disorder and all of those things that people take for granted, all of the things that my peers were doing, even holding down friendships and relationships were almost impossible because of my behaviour, particularly during manic phases.

“So, after I was diagnosed, it really was about being a baby in a man's body, learning how to function in the way that the world expects you to.”

Also on Running Tales:

Rohan told Running Tales there were times on that journey when he felt “absolutely brilliant,” but in other moments he craved the chaos which had previously been his everyday life.

Over time, he started to build a level of resilience: “That taught me so much about just being on your own journey.

“I'd already started, by that point, to do quite a lot of mental health awareness work with Mind. That was at a time where there was still a hell of a lot of stigma attached to mental ill health and mental health as a whole.

“What that taught me was there's no shame for anyone. And I think this is a message that I'd get across to everyone.

“There's no shame in walking, there's no shame in being slower than the person who's in front of you when you go out to run.

“You are not, unless you are Eliud Kipchoge or being paid to do so, you're not in a race. We’ve done really well as a running community to be very inclusive and to encourage people to remember, actually, the competition we're in is with ourselves every day, just to get out there when we feel that the world's looking at us and the world's judging us, just to get out there, persevere, and continue to be the very best we can be.”

‘I couldn’t run a bath’:

Despite not living in London at the time, Rohan became caught up in the excitement of the 2012 Games.

“I wanted to see the greatest show on Earth,” he said.

“Little did I know I would become a perfect example of its legacy.”

But back when he visited the Olympic Stadium, Rohan was “big enough to take up two seats”.

At his heaviest he weighed 19 stone eight pounds, and he told Running Tales that while his mental health had improved hugely since his bipolar diagnosis, he had neglected his own physical wellbeing.

“As we well know, physical and mental health are very, very closely interlinked,” he said.

“It’s a blessing and a good job that I got back hold of my physical wellbeing before my mental wellbeing begun to tailspin again.

“But, going back to 2012, that was when I was at my lowest ebb in terms of physical condition. I couldn't run a bath, let alone anything else.

“We were on the top tier of the stadium and just walking up the stairs left me out of breath.”

Although Rohan was inspired by the Olympics, it wasn’t until six months later that he started to make changes to his life.

After a visit to the doctor was prompted by a flu episode which took two months to kick, he realised it was time to start taking more care of himself.

His first move was to join a 24-hour gym, catching the first bus from his Birmingham home to start exercising at 5.30am every weekday morning.

“That’s where things started,” he said. “For those first few months, it was probably half a minute on the treadmill of what one might loosely describe as running, and then probably followed by about five minutes of walking.”

Rohan gradually began to see improvement but he realised he needed a goal to allow him to continue moving forward.

In February 2013, he entered the Manchester Great Run, which was a 10k event in those days.

With the race set to take place in May that year, he started to up his training - much to the amusement and concern of his friends who “just looked at me, partly in amusement, partly in incredulity and partly in absolute concern that I would just keel over and stop breathing.

Sponsor Rohan to raise money for Mind:

“To be fair to them, I think they always knew that once I put my mind to it I was going to do it even if I crawled it.

“The nickname, of course, quite imaginatively or unimaginatively as the case may be, that they coined for me was Ro Farah.

“I think that journey of recovery was also a journey of discovery. Over time I realised we can overcome things that we don't believe we can.

“Living through that darkness of mental ill health, I'd gone through years where I looked in the mirror and I was either terrified of or hated what I saw.

“And now, it was about could I look in the mirror and love that person and know that person was giving everything that they possibly could?

“If every day without fail, you can do that, it doesn’t matter whether you ‘win’. The reality, as long as you've given yourself every opportunity, is you’re already a winner.”

Rohan was also driven on by a decision to use the event to raise £250 for Mind, the mental health charity, which had provided him with huge support during his mental health crisis, and was to become the focus of many future fundraising runs.

These days he acts as a Trustee for the charity, giving back to an organisation that helped transform his life.

Becoming the marathon man:

That Manchester 10k - completed despite Rohan still weighing 16 stone and having trained only on a treadmill - had captured his imagination fully.

“I think that was one time when my mental health disorder really helped me,” he said.

“I never want to trivialise a manic episode of bipolar because it's a horrible and quite dangerous thing, but actually there are elements of behaviour which contribute to that compulsive side of me.”

An excited Rohan threw himself into more races and more fundraising, entering the Great North Run soon after and then both the Royal Parks and Great Birmingham half-marathons.

Down to around 13 stone, Rohan was feeling fitter and healthier than he had in years. There was really only one next step.

He said: “I rang up the events team at Mind and the lady I knew there said, ‘I know what you're going to ask - April 26 next year, is it?’”

Rohan was going back to London again, but this time it was to run the marathon.

“It was a heck of a journey, he said, “but it's a time in my life which I look back at with a huge amount of fondness and a huge amount of fun for all the things I got right, but all the things that I got wrong as well.

“When I think of it, if I was coaching a runner how to do things now, I'd say don’t do what I did.

“But in the end, it didn't do me any harm.”

The incredible journey which almost went wrong:

With London under his belt, Rohan’s love of running - and marathons - only grew.

These days he has a total of 82 under his belt, with eight more planned for December set to take him closer to that magical 100 target.

“If anyone had told me when I started the journey that this was where it would lead, I would have questioned their own mental wellbeing,” he told Running Tales.

“It’s been an incredible journey and it has allowed me to make a significant contribution to Mind.”

Over the years, Rohan’s marathon efforts became faster, culminating in a personal best of two hours, 57 minutes - an achievement which ended up being a double-edged sword.

“I never aimed to be a sub-three hour marathon runner,” he said

“It crept up on me and happened by accident. In a way, it was great and I'm so proud of it.

“But it also ended up being one of the worst things that could have happened to me, because for a period of time after that it stripped away my love and enjoyment.

“I've never been someone who has a structured training plan. I just go out every day and run how I feel.

“I'm not a professional. I'm just someone who runs for my wellbeing, and that's it. And it stripped away that joy.

“I got to a point where I was constantly needing to prove to myself that it hadn't been a fluke or that I was still as fit as I was at a certain point.

“It was just getting so toxic.”

In 2019, despite not being fully fit, he forced himself round a joyless New York Marathon.

“It was such a shame because New York is one of the great running events in the world,” he said.

“I ran it out of condition, out of form, without enjoyment, because I'd stripped myself of any enjoyment of running.

“It was, well, if I can't run a good time, why am I running a Major?

“None of it made sense. The strange thing was I'd always, with every single one of them, feel joy when I crossed the finish line.

“But it was the build up to it which had become horrible.”

By 2021, Rohan was returning to run London once again. The race was to be his 50th marathon, but he was struggling with a calf injury.

Just seven miles in, his calf popped and he ended up limping his way round. Without the help of St John Ambulance, he probably wouldn’t have finished at all, completing the race in a respectable four hours 11 minutes.

It was to be his last marathon for 18 months.

Rohan had suffered a tear to his achilles, leaving him out of action for the rest of 2021 and the whole of the following year.

“Without a shadow of a doubt, it was the very best thing that's ever happened to me,” he said.

“It repaired a relationship with running which had gone south, and it did so in the most beautiful way.

“I was very clear that my expectations were that I didn't need to run quickly ever again. I just needed to be able to run and enjoy it and have fun.”

Running for the love of it:

Two weeks after returning to running, with a gruelling 10k completed over Christmas 2022, Rohan suffered another setback when he lost his job.

But again, he managed to find positives from the situation. His human resources role had involved long hours, across numerous time zones, meaning a break from such pressure came with mental health benefits.

“When I thought about it, the timing couldn't have been better because it allowed me to step back.

“I was able to commit time to my wellbeing and building up my fitness again, which was a real godsend in terms of structure for me.”

Rohan decided to take a career break, concentrating for much of this year on his work for Mind and on getting fit and running.

Having fallen back in love with the sport, he set his sights on a marathon goal he thought his 2021 injury had taken from him - reaching a century of marathons by the age of 50.

That target has already seen him motor through 32 marathons so far this year, including ten in ten days.

“It’s just been an incredible year and I feel so blessed,” he said.

“To come from a place where I'd fallen out of love with running, because it was making me so anxious before every race, and get back to that point where I can just do it for the love has been a wonderful feeling.”

Considering all Rohan has been through, it’s a legacy to compare to even the London Olympics.

Thanks as ever for reading and listening to Running Tales. We couldn’t do this without your support - please back us to keep going by…